When poverty was a priority

Rural America is hurting, and Washington doesn’t care

By Rick Holmes

March 30, 2018

Johnson City, Texas – It’s no coincidence that the offices of the Pedernales Electric Cooperative sit just across the street from Lyndon Johnson’s boyhood home.

In the 1930s, the Texas Hill Country was like most of rural America: Isolated, dusty and poor, with few jobs and limited prospects, losing its brightest young people to the growing cities. Those left behind still lived pretty much like they had in the 19th century. They didn’t even have electricity, because it cost too much to string wires to houses spread so far apart.

Young Lyndon Johnson ran for Congress in 1937 on a promise to bring power to the Hill Country. He had an ally in President Franklin D. Roosevelt, whose Rural Electrification Administration – one of dozens of New Deal agencies trying to improve the lives of struggling families – provided start-up loans to customer-owned electric cooperatives. Once elected, Johnson got the federal loan and went farm-to-farm talking people into joining the cooperative. Soon enough, folks in the Hill Country had refrigerators, radios and the opportunities that come with being part of the wired world.

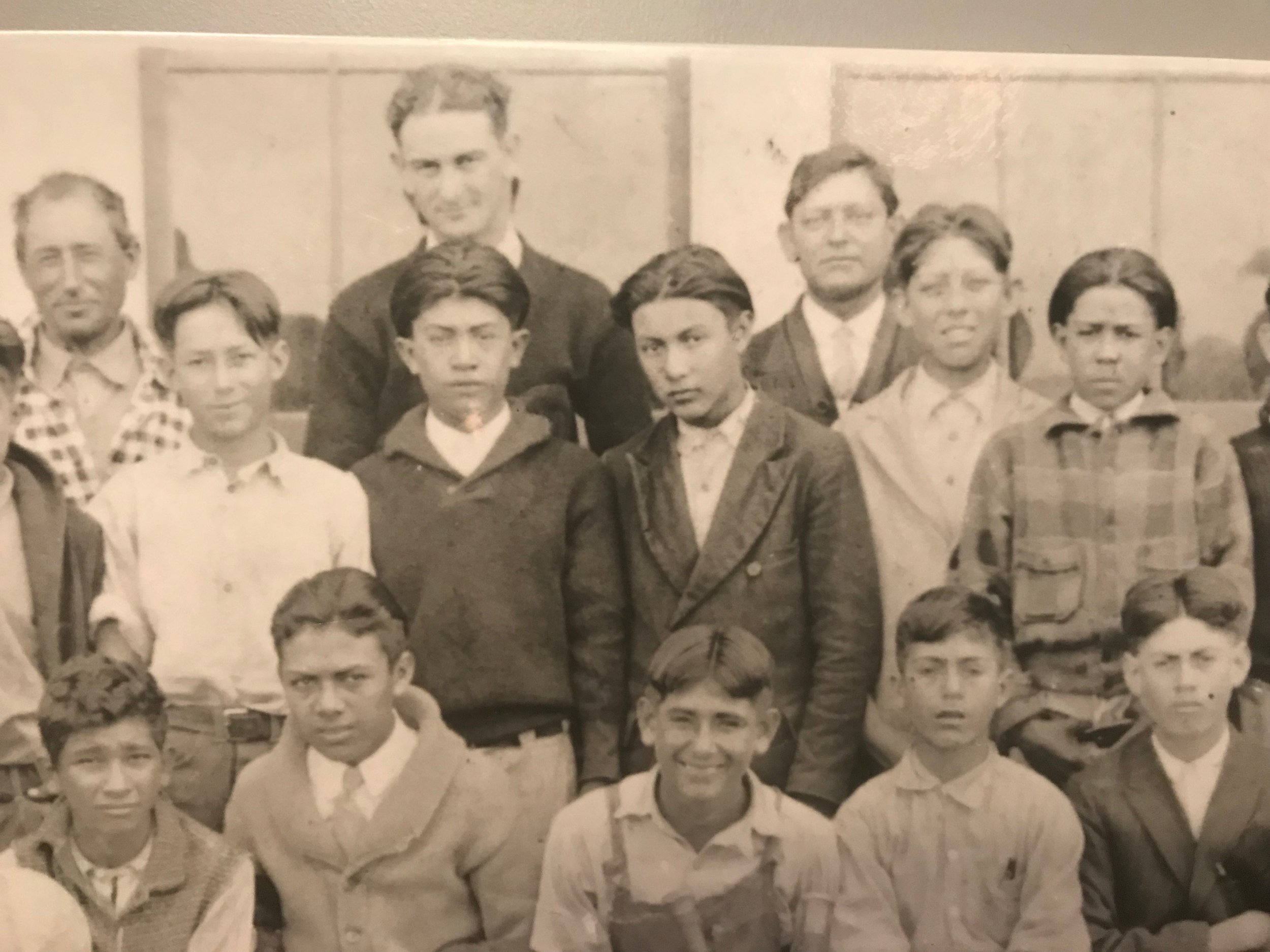

Johnson knew the lives of the rural poor. He taught school in Cotulla, Texas, where his students, nearly all Mexican-Americans, were trapped by poverty and discrimination. He saw the toll taken by underfunded schools and unavailable health care.

A passionate New Dealer, Johnson believed the government could make life better for people his father had described as “caught in the tentacles of circumstance.” In Congress, and especially after he became president on the assassination of John F. Kennedy, Johnson delivered. The domestic agenda enacted under LBJ stands second only to FDR’s in shaping modern America: Medicare and Medicaid to help the sick; food stamps to feed the hungry; Head Start, federal education aid and Work Study to help close the education gap. No president since has come close to his domestic legacy.

Johnson called it the War on Poverty, a term conservative critics ridiculed after he left office, declaring it was a war poverty had won. It was a bad metaphor – war metaphors usually are – because it takes constant effort to minimize poverty, and there’s no final victory. But while he was in office, the percentage of Americans living below the poverty line fell from 23 percent to 12 percent, no mean accomplishment. Johnson cut poverty in half, and if Vietnam had not derailed his presidency, he likely would have cut it more.

“I hope it may be said, a hundred years from now, that by working together we helped make our country more just, more just for all its people, as well as insure and guarantee the blessings of liberty for all of our posterity,” Johnson said as his presidency drew to a close. “That is what I hope.

“But I believe that at least it will be said that we tried.”

In my travels across America over the past year, I’ve seen a lot of places where the main commerce seems to be dollar stores, pawn shops, payday lenders and disability claims. Further from the interstates there are no signs of economic life at all.

Rural America is hurting today, at least as much as back in the 1930s. Jobs have been lost to trade and mechanization. Family farms have been lost to corporatization. Rural America is steadily losing population, as bright and ambitious young people flee to cities and suburbs. Those left behind are isolated from the global economy, dependent on government benefit programs and increasingly addicted to opioids.

Persistent poverty, passed down from generation to generation, comes in all colors: white in the hollers of Appalachia, black in the Mississippi Delta, brown in the Rio Grande Valley, red on the Indian reservations of the west. As in the ‘30s, discrimination strengthens poverty’s grip.

The difference is that today, nobody in Washington is fighting to get high-speed Internet into rural towns like LBJ fought to bring electricity to the Hill Country. There’s no national plan to break the opioid epidemic or revive communities on the brink of becoming ghost towns. Rural voters are fed culture wars rhetoric by Republicans and mostly ignored by Democrats. When it comes to rural poverty, neither party has a plan.

There are no easy answers. Some of LBJ’s War on Poverty programs came up empty. But at least he and Congress made the effort. What deepens the desperation of the nation’s rural poor today is that Washington doesn’t even seem to be trying.

Rick Holmes can be reached at rick@rickholmes.net. You can follow his journey at www.rickholmes.net. Like him on Facebook at Holmes & Co, on follow him on Twitter @HolmesAndCo.