Living history

In Charleston, the past is always present

By Rick Holmes

Dec. 15, 2017

Charleston, SC – This is a place where the present constantly collides with the past.

Children play on the cannons that long defended Charleston Harbor. A statue nearby honors the city’s “Confederate Defenders.” Steps away is a stone marking the spot where Stede Bonnet, the “Gentleman Pirate” and 29 of his mates were hanged in 1718. The prices of the houses nearby on South Battery, we’re told, have recently gone through the roof.

We pass an antebellum mansion surrounded by wrought-iron fences that look like barbed wire. The style was a response to wealthy Charlestonians’ fear that the slaves would revolt and come after them, we’re told. In 1822, Denmark Vesey, a slave who had bought his freedom with lottery winnings, plotted a slave uprising that was thwarted at the last minute. He too was hanged, along with 35 others said to be co-conspirators.

We walk past the old Slave Mart, where thousands of kidnapped Africans were sold to the highest bidder, and the Museum of the Confederacy, where two Daughters of the Confederacy spoke of slaves who joined their “best friends” – their masters – to go off and fight the invading Northerners.

We walk by TV news vans parked near the federal courthouse. Michael Slager, a white police officer, is being sentenced for killing an unarmed black man, Walter Scott, in North Charleston last year. A bystander’s cell phone video showed Slager pumping five bullets into Scott’s back from 17 feet away. That may be history, too: The judge sentences Slager to 20 years, which is by far the heaviest imposed since officer-involved shootings sparked the Black Lives Matter movement.

We stay in a most pleasant campground in a town called Mount Pleasant, just over the Cooper River from Charleston. It’s connected to the city by the Arthur Ravenel Jr. Bridge, a magnificent span completed in 2005 at a cost of $700 million. Since then, Mount Pleasant has one of the fastest growing communities in the country, with condo complexes and big box stores sprouting on both sides of Rte. 17.

Everything around here is called a plantation, even if it’s really a subdivision or a gas station, but the campground where we stay is part of the real thing, the Oakland plantation, which dates back to 1713. Generations of black slaves and their white owners grew indigo, tobacco and cotton there.

The plantation has been in the Porcher family since before the Civil War. The Porchers weren’t home when the Union army came through, burning its way to the sea. Col. James Beecher – brother of Harriet Beecher Stow, a literary historical figure - found four slave families living in the main house, they say, and in deference to his wife’s abolitionist sentiments, chose not to destroy it.

Somehow the Porchers and their descendants, the Gregories, managed to hold on to Oakland through the tough times that followed the war, with the help of former slaves who became tenant farmers. Then the Ravenel Bridge was built. Now the Oakland Market sprawls alongside Rte. 17, and the plantation owners harvest lease payments from the likes of Walmart and Kohl’s, along with campground fees from travelers like me.

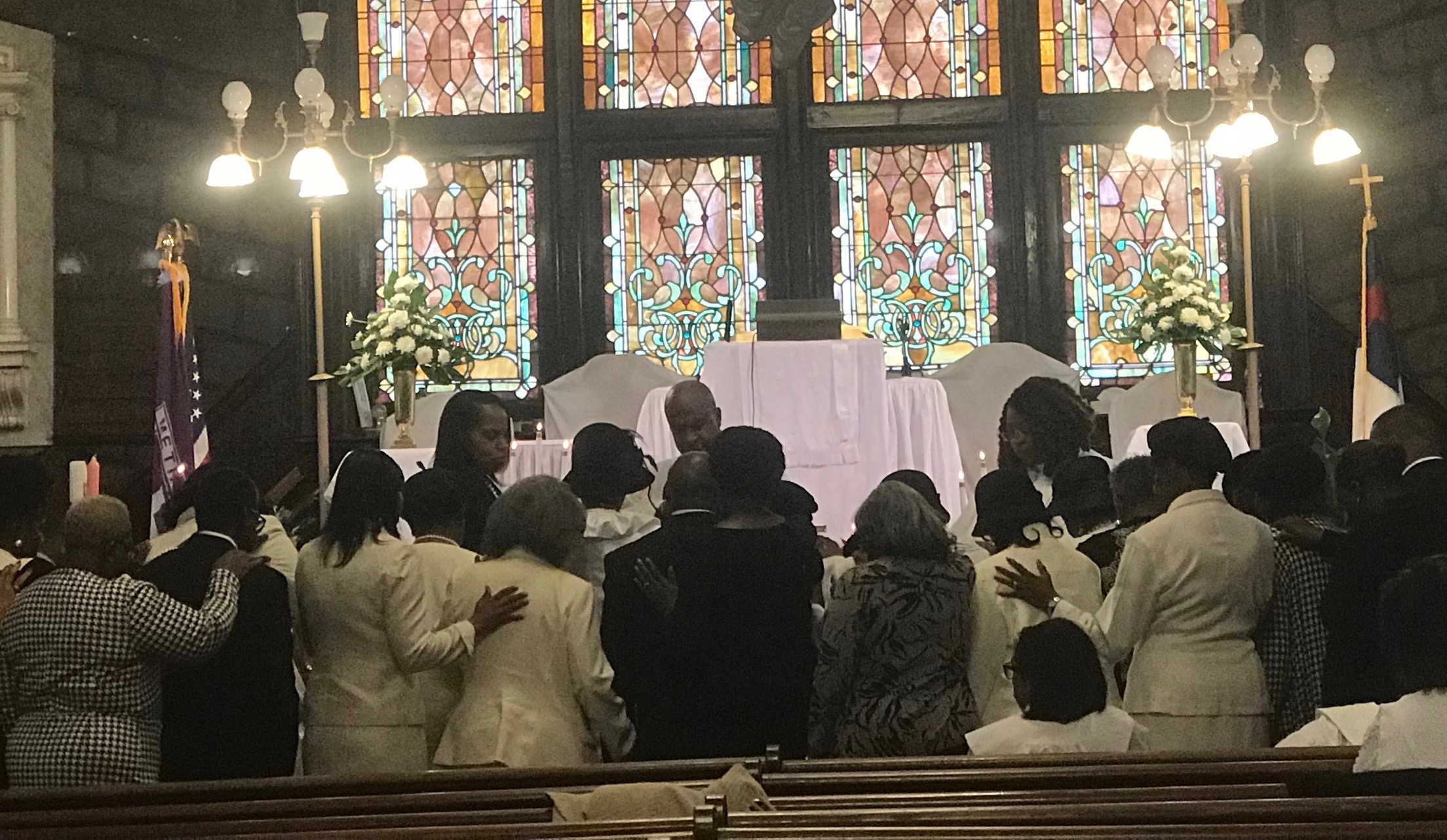

On Sunday, we attend services at Emanuel Church AME. The sanctuary is decorated for Advent, and the music and preaching lift us up. Mother Emanuel, as it is known, was founded in 1818 by Denmark Vesey, among others. After the failed slave uprising, a mob burned down the original church. The congregation kept meeting underground, and built a new church after the end of the Civil War.

In 2015, Dylann Roof, a young man who liked waving the Confederate flag, came to Mother Emanuel, in part because of its long history, and proceeded to murder nine people who had invited him to join their prayer meeting. Today, Mother Emanuel carries on.

At Fort Sumter, I ask a ranger if we should visit Fort Wagner, site of a climactic battle involving the famed Massachusetts 54th Regiment. Sure, he says, but it’s 1,000 feet underwater. Rising sea levels threaten Sumter as well: Researchers estimate its historic parade ground will be submerged by the end of this century. When “king tides” hit, the sea invades Charleston’s streets.

Charleston is a city that wears its history well, especially downtown, where no building can be taller than the highest church steeple. A mid-19th century style is draped over downtown like Spanish moss over a live oak tree. Spanish moss doesn’t hurt the tree; it just makes it something more, something special.

But Charleston is not trapped in time. The horror at Mother Emanuel, a deadly police shooting, economic growth and the rising seas point to a city very much a part of the 21st century.

History doesn’t stop, even in places where it is most carefully preserved. We’re still making it, every day.

Rick Holmes can be reached at rick@rickholmes.net. You can follow his journey at www.rickholmes.net. Like him on Facebook at Holmes & Co, on follow him on Twitter @HolmesAndCo.