The politics of a mountain’s name

Let Denali always be Denali

By Rick Holmes

Aug. 31, 2018

Talkeetna, Alaska – This is a small frontier town, lacking in amenities like sidewalks, storm drains and paved parking lots. So we slogged through the Alaska mud to get to the rain-swollen Susitna River.

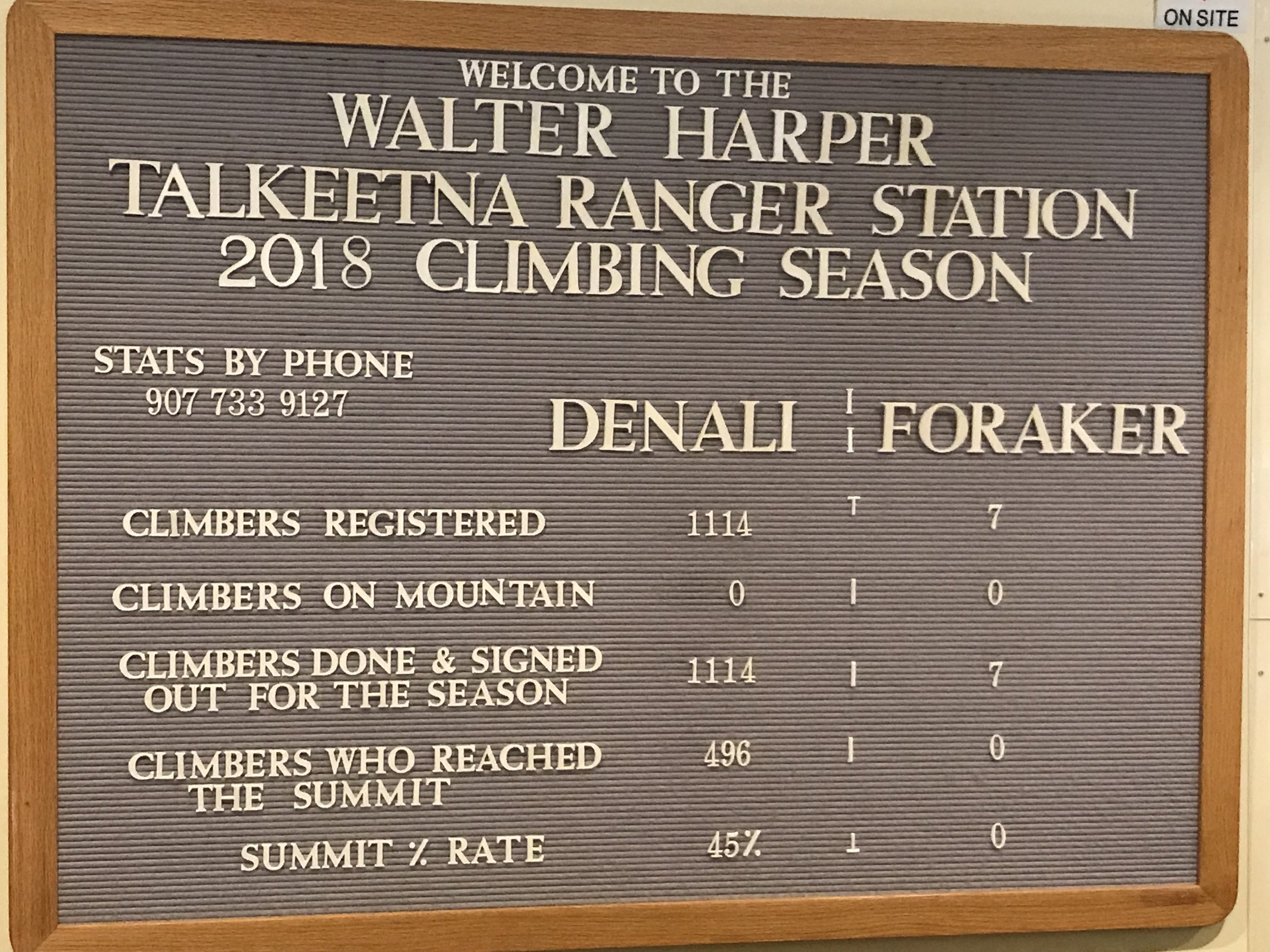

On the other side, wrapped in clouds, is the reason people come to Talkeetna: the highest peak in North America. Mountain climbers from all over the world go from here to the glacial base camps where they begin a grueling, two- to three-week hike to the summit. About half give up before reaching the peak.

For 10,000 years, the Athabaskans called the mountain Denali. For 100 years the federal government insisted it be named for a politician from Ohio who had nothing to do with either the mountain or Alaska.

Talkeetna’s got a lot of personality. “Northern Exposure,” a 1990s TV show about eccentric and adventurous people in small-town Alaska, was inspired by Talkeetna, they say, and that’s what it feels like in the Fairview Inn. Mario Carboni, with a voice like Merle Haggard and a piano like Jerry Lee Lewis, has the place rocking. Everyone seems to know each other, or at least they act like they do.

A young man I’d never met points to a dusty photo on the wall. “That’s President Warren Harding,” he says. Harding came to Talkeetna when he was president, ate dinner in this very room, then went upstairs and died. Food poisoning, he says. Talkeetna did him in.

It’s a good story, partly true. Harding, the first president to visit Alaska, came through Talkeetna in 1923 on a western tour. But Harding had many ailments, including a bad heart, long before he reached Talkeetna. He likely left the Fairview Inn feeling sicker than when he arrived, but he didn’t die until he reached San Francisco a week or so later.

But if all he did was eat some bad crab legs in Talkeetna, Harding still has a greater claim to having mountain named for him than William McKinley. That deal was political from the beginning. William Dickey, a prospector during Alaska’s Gold Rush, announced in 1896 that the mountain had been named for the Ohio governor, then running for president, in recognition of his support for the return to the gold standard, an issue near and dear to the hearts of Alaskan gold prospectors.

Dickey’s proclamation carried no legal weight, but it acquired it along the way. In 1917, Congress made the honor official, naming the mountain and the new national park surrounding it for McKinley.

Alaska didn’t have any say in it. It was still a territory at the time, with no votes in Congress. Certainly no one asked the Athabaskans about it. Native Americans in Alaska weren’t even allowed to vote until 1922.

But Alaskans of all kinds can be stubborn. They never stopped calling the mountain Denali, and never stopped resenting Washington’s intrusion. In 1975, Alaska’s legislature officially requested the mountain to be renamed. There was resistance, though, in the form of Ralph Regula, the Congressman from Canton, Ohio, McKinley’s hometown. Regula used parliamentary maneuvers to stall attempts to change the name from 1975 until he retired in 2009.

The Alaskans persevered. In 1980, Jimmy Carter signed a law expanding the national park and renaming it Denali National Park and Preserve. Then, in 2015, Barack Obama came to Alaska to announce his administration was officially changing the mountain’s name to Denali.

That should have been the last of it, but a longshot presidential candidate disagreed. "Great insult to Ohio,” tweeted Donald Trump. “I will change back!"

He hasn’t yet. Since he took office, Trump reportedly asked Alaska’s two senators if he should name it Mount McKinley again, and they said no. Sens. Dan Sullivan and Lisa Murkowski say Trump agreed to leave the issue alone, but the White House won’t confirm it. Since then, 11 members of the Ohio delegation have weighed in on the other side, asking Trump to reverse Obama’s “disrespectful” decision and “preserve William McKinley’s legacy.”

And they say Washington won’t tackle the big issues.

I’ve been to Canton, Ohio. I’ve climbed the mini-mountain that leads to McKinley’s opulent tomb. Canton is a fine city with much more important things to worry about than perpetuating a cartographical footnote that has nothing to do with McKinley’s real legacy. Friends in Canton tell me most folks would probably side with the Alaskans if they thought about the issue at all.

But Alaskans do care, about their land and their history, Hudson Stuck, an Episcopalian missionary in central Alaska who, in 1913, led the first expedition to reach Denali’s summit, expressed it well:

“It may be that the Alaskan Indians are doomed,” despite all the efforts to save them. “But if it be so,” Stuck wrote, “let at least the native names of these great mountains remain to show that there once dwelt in the land a simple, hardy race who braved successfully the rigors of its climate and the inhospitality of their environment… And flourished.”

Rick Holmes can be reached at rick@rickholmes.net. You can follow his journey at www.rickholmes.net. Like him on Facebook at Holmes & Co, on follow him on Twitter @HolmesAndCo.