History and legend in the Wild West

By Rick Holmes

April 13, 2018

Lincoln, NM – The main road through town is paved now, but otherwise looks much the same as when the president of the United States called it “the most dangerous street in America.”

The buildings that line the street look like they did when armed gangs shot up the place 140 years ago. Those built since, small structures of warm brown adobe, look just as old. There’s not a gas station, convenience store or motel in sight.

On one side of the street is the two-story building that used to house the operations of the Murphy-Dolan gang. They controlled the commerce in Lincoln County, starting with the contracts they won to supply nearby Fort Stanton and the local Indian Agency. They were rich, powerful, corrupt and violent.

On the other side is the store opened in 1876 by John Tunstall, a young Englishman who was determined to build his own empire in Lincoln County. The competing outfits went after each other with lawyers and guns. After Tunstall was murdered, his friends – including the gunslinger you know as Billy the Kid – became the Regulators. They were interested less in profits than revenge.

The Lincoln County War featured real events that became movie cliches. There were gun battles fought at full gallop, drunken cowboys shooting up the town, and a well-intentioned lawyer or two who paid for their naiveté with their lives.

Over there stood the McSween house, set on fire in the midst of a shootout to drive out the gunmen inside. Steps away is the spot where Billy and his friends ambushed Sheriff William Brady, killing him and one of his deputies.

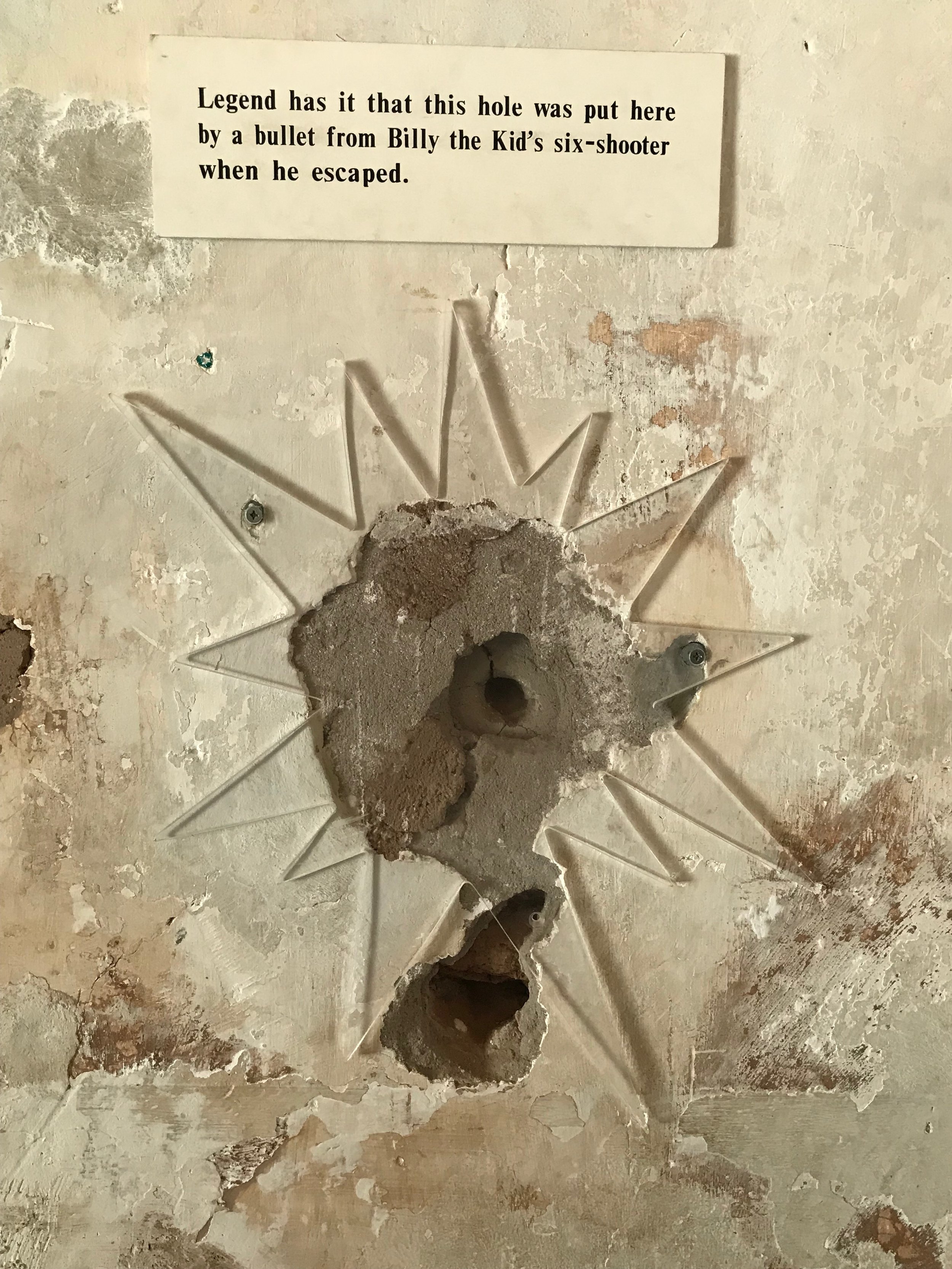

Billy was later captured, convicted and sent back to Lincoln to be hung. In the building over there, he overpowered the deputy who had escorted him to the privy and shot him dead with his own gun. You can still see the bullet hole in the staircase wall. When the other deputy came running across the street, Billy shot and killed him, too.

The gun violence in Lincoln made headlines around the country before the smoke had cleared. Readers as far away as Europe followed the adventures of Billy the Kid. Pat Garrett, the Lincoln County sheriff who caught up with the Kid, ambushing him when he came to visit his sweetheart, wrote one of the first best-sellers about Billy’s life, and many more followed. Then came the movies and TV shows.

Historians of the Wild West, of which there are many, consider most of the early accounts more fiction than fact, and don’t even get them started listing the inaccuracies in the movie versions. The real stories can still be entertaining, if told by a gifted storyteller, but the legends lose their nobility when looked at closely, and their tragedy looks more like farce.

Keep in mind that during most of these gunfights, historian and storyteller Drew Gomber told a recent gathering in Lincoln, the shooters were usually drunk, which is why so many of their shots didn’t hit anyone. “It’s no coincidence that almost all the violence in the Old West happened around saloons,” he said.

To a historian, the Lincoln County War is about what happens when corrupt capitalism meets gangs of drunken young men, adolescents with too little impulse control and too many guns. The same forces operate in urban street gangs today.

The real William Bonney was a murderer and a cattle thief, unworthy of anyone’s admiration. But even while he was still alive, the mythmakers were turning him into something else. Billy the Kid became an American icon: The loner, the drifter, who is loyal to his friends, kind to the locals and good with a gun. People have been making money off of that Billy the Kid for 140 years.

They still are. Lincoln’s main street is now officially Billy the Kid Trail, part of the Billy the Kid National Scenic Byway, which connects various sites around Ruidoso, a growing mountain resort town here in south central New Mexico. In the one known photograph of Billy, he looks homely and kind of dim. But the tourist industry has cleaned him up considerably in their recent promotions.

The Wild West doesn’t hold the prominent place in popular culture it occupied 50 years ago, but the themes still resonate with audiences. The heroes in today’s movies are also often outlaws; they just have more powerful weapons. The myth-making industry controls the narrative, not the historians.

In “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valence,” one of John Ford’s classic westerns, the disillusioned lawyer asks the cynical newspaper man if the real story of the town’s epic shootout will ever be told. “This is the West, sir,” the editor replies. “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

Rick Holmes can be reached at rick@rickholmes.net. You can follow his journey at www.rickholmes.net. Like him on Facebook at Holmes & Co, on follow him on Twitter @HolmesAndCo.