The ghosts on the hill

By Rick Holmes

Jan. 11, 2019

Montgomery, Alabama – The arc of the moral universe bends over downtown Montgomery.

It starts at the foot of Commerce Street where, at the height of the domestic slave trade, hundreds of enslaved people were herded off trains and riverboats every day for sale at the city’s slave markets. It bends over the milky white dome of the Alabama State Capitol, where, in 1861, the Confederacy was born.

Markers of injustice and protest huddle close together in Montgomery. Looking down from the gold star on the Capitol steps that marks the exact spot where Jefferson Davis was sworn in as first president of the Confederacy, you can see the red brick church, a short block away, where the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. launched the modern Civil Rights Movement.

Six blocks from what is now called the Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church is the corner where, in 1955, Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to give up her seat on the bus to a white person. King led the organization that called on Montgomery’s African Americans to boycott the city buses. The boycott held for more than a year, until courts ordered city buses be desegregated.

Over on Jackson Street is the parsonage where King and his young family lived while he served at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church. You can sit at the kitchen table where he agonized during the bus boycott over the constant threats to himself and his family. You can see where a bomb exploded on his front porch.

Two blocks from the Rosa Parks Museum is the old Greyhound bus station where, five years later, Freedom Riders determined to desegregate interstate bus travel were beaten by a white mob while Montgomery police were suspiciously absent.

On Dexter Avenue, painted footprints mark the culmination of the 1965 march from Selma to Montgomery. Klan murders and police brutality had failed to stop a march for voting rights that had stirred the conscience of the nation. King addressed the throng from the back of a flatbed truck parked in front of the Confederacy’s first capital.

“How long will justice be crucified?” King asked the crowd. “Not long,” he answered, “because the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”

A half-century later, as tourists move between historical markers, museums and shrines, we can see this as a story with a happy ending. Four months after the marchers reached Montgomery, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was signed into law. The good guys had defeated Jim Crow. Justice was done.

To which the ghosts on the hill say “Not so fast.”

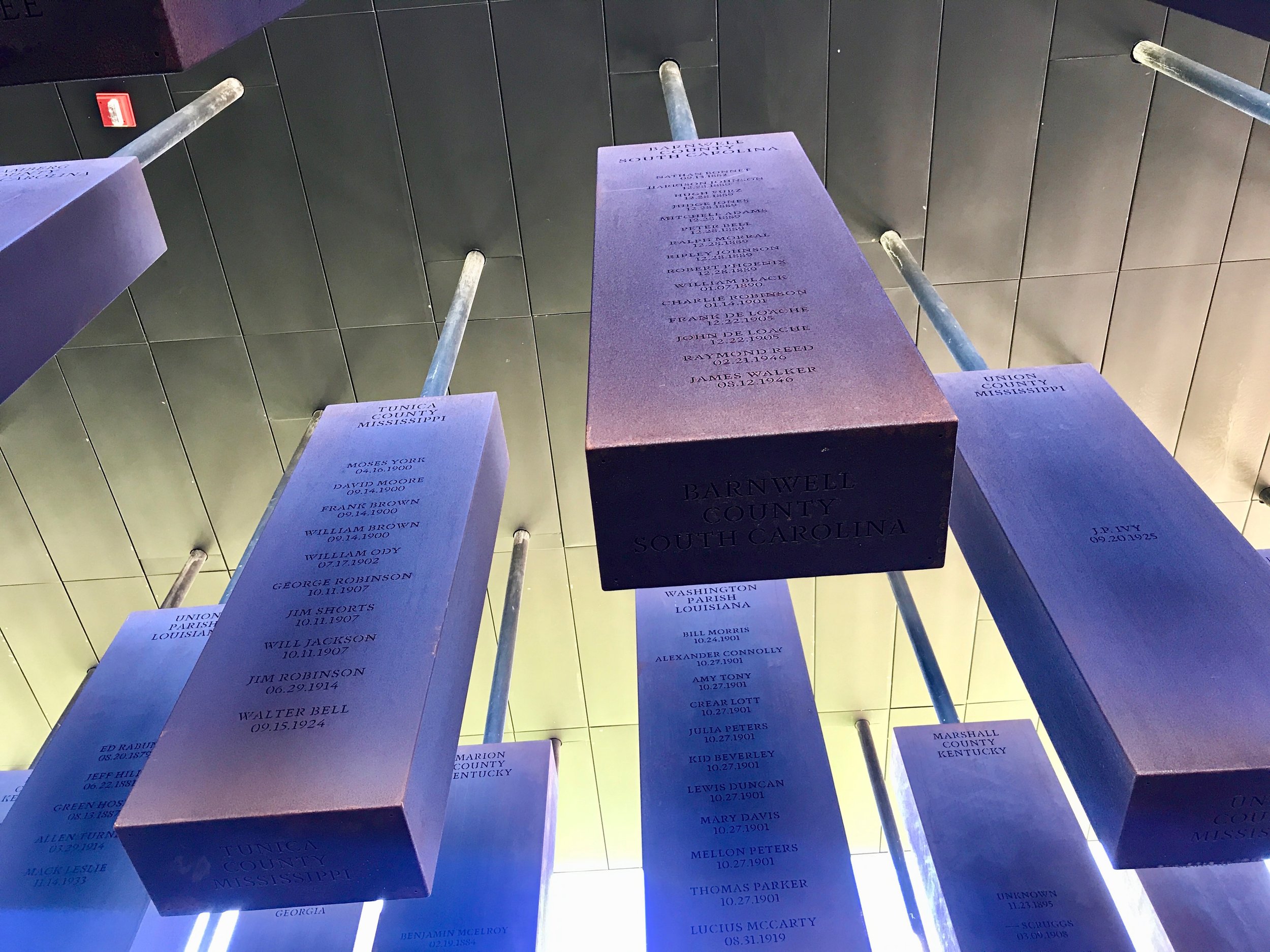

The ghosts on the hill hover over Montgomery’s newest destination, the National Memorial or Peace and Justice. There, 805 steel slabs the size of coffins hang in neat rows. On each is engraved the names of people killed in racial terror lynchings in each U.S. county where such murders occurred.

Signs below tell the stories of some of the people whose names are suspended above. There’s Henry Bedford, 74, lynched in 1934 or “talking disrespectfully” to young white men; Elizabeth Lawrence, lynched for “reprimanding white children who had thrown rocks at her”; General Lee, lynched in South Carolina for knocking on a white woman’s front door; Mary Turner, lynched in Georgia for complaining about the lynching of her husband.

The impact is powerful, and personal. I walk among the dead, thinking “how could my people have done this?”

The hanging slabs are arranged around a square, a reminder that hanging, mutilating and setting African Americans on fire was often a public act, carried out in a courthouse square. People brought picnic lunches and collected picture postcards of the grisly scenes, and not just in the South. In Minnesota, Kansas and Colorado, crowds in the thousands watched black men hanged by the neck and burned alive.

There had been no justice for these Americans. No judge or jury had heard their defense. No police had investigated their alleged crimes. In many cases the police were among their killers, only sometimes hidden behind Ku Klux Klan masks.

The ghosts on the hill remind us that, as King said, “True peace is not merely the absence of tension. It is the presence of justice.”

But how do you deliver justice for the more than 4,400 men, women and children hanging on the hill, victims of a reign of terror waged to subjugate an entire race? What can be done for the countless others whose murders were never recorded?

We start by bearing witness to the crimes committed by Americans not so long ago, by keeping their stories alive.

We honor them by recognizing racial injustices in our own time that echo the experience of African Americans: police brutality, racial profiling, for-profit prisons, mass incarceration.

And we bring justice by remembering that civil rights is a cause, not a history lesson. The moral arc of the universe doesn’t bend by itself, as King and those who marched with him understood. We have to bend it.

Rick Holmes can be reached at rick@rickholmes.net. You can follow his journey at www.rickholmes.net. Like him on Facebook at Holmes & Co, on follow him on Twitter @HolmesAndCo.