10. House of Oma

Oma Grier and Mabel Davis had five children: Mabel Boyd Davis Jr., who went by Mame; Allie Coleman Davis (my mother); Lily McFadden Davis; Oma Grier Davis Jr., who went by Grier, and Charles Robert Davis, who all knew as Chick. They grew up sharing Davis values: Family, church and education. They moved a lot around the South, but had little connection to the family’s Arkansas roots except for vacations and family reunions, typically held in Hot Springs. A historic event would scatter them further: World War II.

Mame, the oldest, titled her book of recollections “Memoirs of a Blond Angel,” which is what her father used to call her. She had a serious bout with scarlet fever and encephalitis when she was 11, which set her back in school. A doctor told her parents the high fevers had likely caused brain damage, a diagnosis her parents never shared with her, but which colored their expectations. She missed more than a year of school, but her strong-willed father, ever the educator, pushed her to catch up. She ended up graduating from high school and college alongside her sister Allie.

Allie was a bright student, near the top of her class. After high school in Jennings, La., she and Mame attended Belhaven College in Jackson, Miss. Mame and Allie sang duets together from the time they could barely climb onto a stage. They sang church music and sentimental tunes, some silly numbers in Andrews Sisters-like harmony. Aunt Mame used to sing some of them to us when we were kids: “Operator, Give Me Heaven,” “Babes In The Woods,” and “The Dummy Line.”

They studied music and education at Belhaven and were likely there in 1933 when the world’s first “singing Christmas tree” debuted.

In their sophomore year, the Depression hit. Banks closed, church offerings dried up, and there was no money for college tuition. Mame and Allie dropped out of Belhaven, took a summer of intense education instruction in Lafayette, La., and by fall were certified to teach in Louisiana. They taught for awhile, saving up enough money to complete their studies at Belhaven.

After college, the sisters got jobs teaching in Cajun Country, deep in the bayous south of Lake Charles, La., where they were soon joined by sister Lily. They taught in Cameron, Golden Meadow, communities that today are battered by hurricanes and losing dry land daily to climate change. Mame taught in Hackberry, further into the sticks, “so saturated with oil that black patches could be seen many places where the land was low, and needless to say, there was no effort at beautification.”

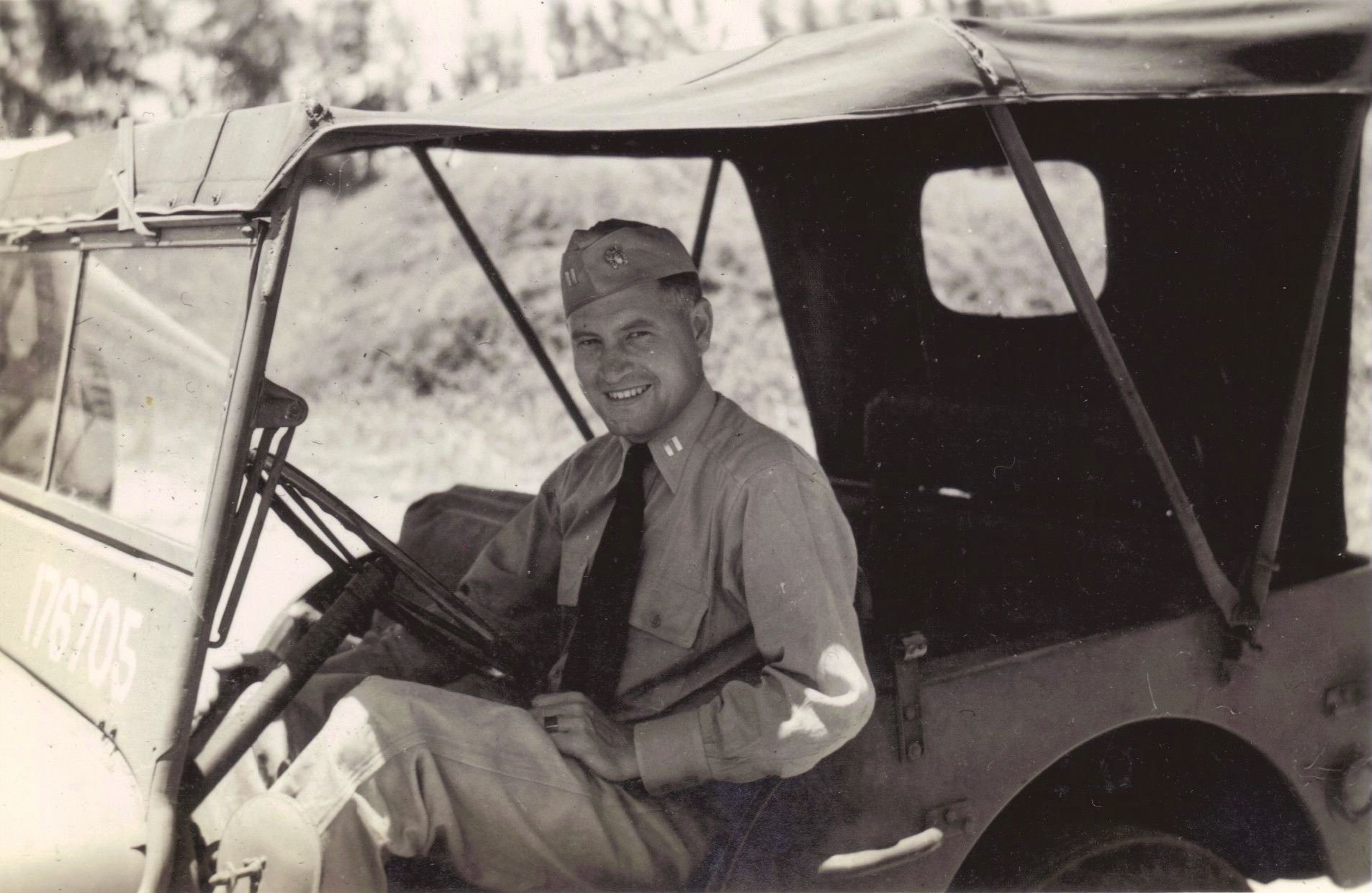

Mame grew tired of Hackberry and school teaching, and enrolled in a two-year program in Richmond, Va., to get certified as a director of religious education. On her return to Baton Rouge she met the love of her life. His name was Edwin Griffith, but everyone called him Griff. He was from southern Mississippi, worked at a local creamery and had just joined Northside Presbyterian Church, where O.G. Davis was pastor. Griff did it all at Northside: attended every service, the Young People’s meeting on Sunday nights. He was a leader in the Men’s Club and in line to become an elder. By Christmas that year, he and Mame were very much in love. With Dr. Davis’ consent, they agreed to be married. Then came Pearl Harbor. Griff enlisted in the Marines and trained to be a medic.

Lily also wanted more than a low-paid job in a little Cajun school. She wanted to be an artist, but got it into her mind that she should learn some office skills first. She worked as a secretary in the Statehouse for awhile, then, after Pearl Harbor, she answered a call from President Roosevelt’s National Youth Administration to come to Washington in support of the war effort. She worked at the Pentagon, which was being built around her as she typed, and she attended art school at night. Sundays she could be found at the Church of the Pilgrims in Northwest Washington, a Presbyterian congregation well-known and recommended by her father. Church of the Pilgrims had a vibrant Youth Group that became a social center for some of the thousands of soldiers and “government girls” flooding the nation’s capital.

At Church of the Pilgrims, Lily met Lorenzo Goodwin Smith, who everyone called Bub. They became engaged just as Bub was entering the Air Force. They were married in May of 1944, and Bub shipped out.

Brother Grier was also going into the Air Force. Between college and flight school, he had visited Lily in Washington, where he also met his mate: Fay Findlay was Bub Smith’s half-sister. Soon Grier and Bub were fast friends considering the prospect of becoming double brothers-in-law, like Grier’s ancestor, Robert G. Davis and William Nelson. But first there was a war to fight.

Allie came to Washington with her father while O.G. filled the pulpit at Church of the Pilgrims in the summer of 1943 and returned for Lily’s wedding the next spring. Along the way, she met a Sunday night Youth Group regular, a Navy officer from Springfield, Massachusetts, named Bill Holmes. Because he had a business degree and a management job at a paper company, he was assigned to the Navy Department’s procurement office, where he helped manage the greatest military buildup in the history of the world. He wanted to get into battle, but first he had to build the ship that would take him there. That turned out to be the U.S.S. Antietam, the aircraft carrier he took from the Philadelphia shipyard to the other side of the world.

And so the men went off to a war that had already turned everyone’s lives upside-down. I have a letter Griff wrote to Mame as he headed for the Pacific:

My Darling,

Well here I am, aboard ship and as you guessed it, I’m not going for a pleasure ride…

You know Beloved, we have quite a few bonds together and if I shouldn’t come back you would probably wonder how to use them since our plans would be shattered. Well, I have thought of this quite a bit and I can’t think of any better thing to use it for than to help our church expand. The little buildings of Northside could stand enlarging and I’d like to help.

In your last few letters you were clearly worried. You said you were! I want you to stop it Dear. I’m not worried – in fact, my morale is high – but I worry to know that my Dear one worries.

In fact, to worry would be in vain for possibly before you get this D-day may have come and gone – I don’t know when they plan to mail this.

The European invasion has come – I’m glad and I hope it continues to do well. I wonder if Oma, David and Charles were in it.

I’m getting a wonderful sun tan now Honey, you really should see it!

Forever yours, Edwin

Edwin Griffith, 22, was on his way to what has been called the “Pacific D-Day,” the invasion of Saipan, one of the bloodiest and most critical operations of the war. Griff was on stretcher duty, carrying the wounded off the beach, when he was struck and killed by a Japanese artillery shell.

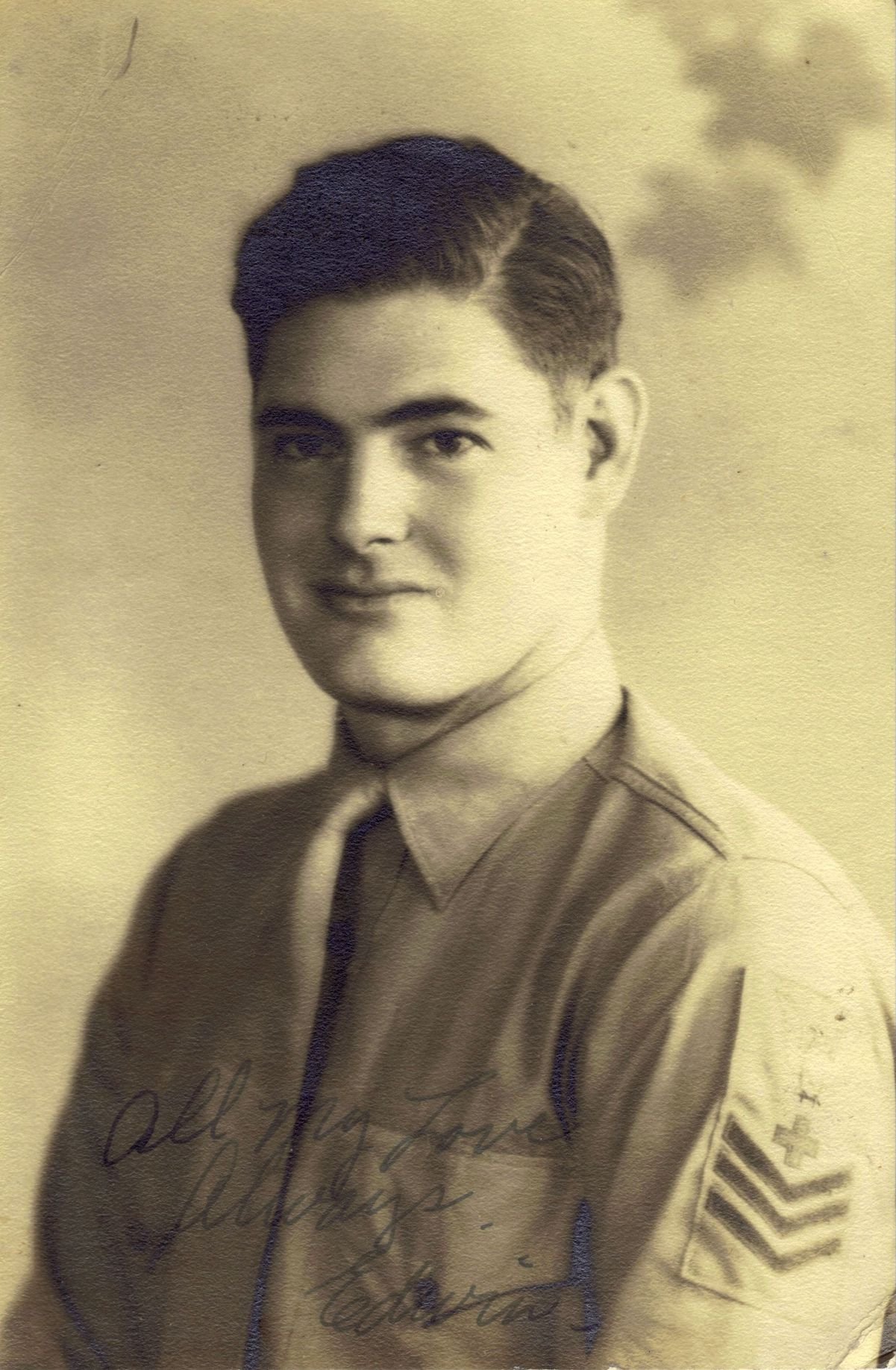

Oma Grier, also 22, went to Europe, where he flew 57 missions in B-26 bombers, three of which ended with him bailing out. After the liberation of Paris, he flew a fighter between the legs of the Eiffel Tower. Passing through England on his way home, he was able to spend a day with Bub Smith, his future brother-in-law.

Lt. Lorenzo “Bub” Smith, also 22, flew B-17 bombers out of England. On April 19, 1945, as Allied armies closed in on Berlin and Americans mourned the death of Franklin Roosevelt, Bub’s plane was shot down over what is now the Czech Republic. Back home in Baton Rouge his wife Lily got the telegram listing him as Missing in Action. Their son, Andrew Grier, had been born a month earlier, the first cousin of a new generation of Davises.

Lt. William Holmes, 32, watched the USS Antietam go from keel-laying to ceremonial launch in just 17 months. He took it on its shakedown cruise, to the British West Indies, back to Philadelphia for outfitting, then through the Panama Canal and on to Pearl Harbor. That’s where he was when American planes dropped nuclear bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The Antietam was three days out of Oahu, on the way to support the invasion of Japan, when word reached them that Japan had surrendered. It went to China instead, where its planes helped keep an eye on Mao Zedong’s rebel army, then to Japan to support the occupation.

On Christmas Day, the Antietam was decorated for the season as it sat at anchor in Tokyo Bay, with a 16-foot electric star high on the mast, colored lights on the gangway and a huge “Merry Christmas” sign on the quarterdeck. Bill played the organ and sang in the choir for the Christmas Eve candlelight service and the Christmas morning communion service. He toured Tokyo, reporting in a letter to Allie that “I seem to recall estimating in the neighborhood of 50% destruction in Tokyo, but now I’m sure that’s low. Took a sight-seeing bus trip around the city, and I’m convinced now that 70-75% would be nearer correct. It’s amazing to see acre after acre completely demolished.”

Bill and Allie had only seen each other face-to-face for eleven days, by his count, when she went back home and he went off to war, but they kept up their correspondence. She always said it was her duty to write letters to several service members and he was just one. But by the end of 1945, his intentions were becoming clear. Discharged in San Diego, he stopped in Baton Rouge on his way home, and they soon began planning a June wedding.

It was a fraught moment for the Davises. Mame was in mourning; she never fully recovered from Griff’s death and never married. O.G.’s heart problems were getting worse. Lily waited in vain for word that Bub had been found, either alive or dead, just as her great-grandmother had waited for her son Billy to come home from the Civil War. But at least the war was over, new marriages were beginning and grandchildren were on the way.

The “House of Oma,” as the five children and their descendants were known at the large Davis reunions, spread far and wide. Grier and Fay moved to Princeton, N.J., where Grier attended Westminster Choir College, and Lily joined them there, building a small house that would be used in turn by Mabel and Mame, then by Chick, who went to Westminster as well. Grier got a doctorate in music and taught in Iowa and New Mexico before finding a second career in home construction in Albuquerque.

In Princeton, Lily met an Army officer studying to be a nuclear physicist. Glenn Brunson had left his family’s huge West Texas ranch to become a scientist, a calling that took him, and his and Lily’s growing family, to Idaho, Austria and, eventually, to Los Alamos, New Mexico, formerly a secret city where the atomic age was born. They built a beautiful house on the edge of the Rio Grande Canyon, where Lily had a large studio for her work in oils, fabric and stained glass.

Mame stayed with her mother until Mabel’s death, then with her brothers and sisters before finding a place in a residential school in Pennsylvania. Chick became the third Dr. Davis, and spent his career teaching and conducting at a small college in Southwest Virginia.

Bill went back to the paper company where he’d worked before the war. He and Allie raised their five children in New England and retired to Lenox, Massachusetts. Allie never fully lost her soft southern accent.