Buffalo, then and now

By Rick Holmes

June 15, 2018

Buffalo, NY – Nothing preserves the past like poverty. Beautiful cities like Savannah, Ga., and Natchez, Miss., retain their historic buildings in part because their fall from great wealth was so steep and long-lasting that no one could afford to replace old structures with new ones.

Here in Buffalo, architectural treasures from another age haven’t been replaced or overshadowed by modern glass towers. They still stand, telling the story of Buffalo’s glory days. There’s Electric Tower, built in 1912, when Buffalo was a leader in the adoption of electricity, thanks to the current flowing from nearby Niagara Falls. There’s Buffalo Central Terminal, 17 stories tall, a reminder that Buffalo was a railroad hub back when prosperity followed the rails.

Infrastructure built Buffalo. It was laid out at the western end of the Erie Canal, the 19th century’s greatest infrastructure project. The canal, which opened in 1825, made it possible to travel by boat from New York City to the Great Lakes. For more than a century, goods from the Midwest and settlers from the East passed through Buffalo, and the city prospered.

That prosperity shows in the stately buildings downtown, built for banks and insurance companies that long ago moved out. It shows in Buffalo City Hall, a 32-story Art Deco masterpiece. It’s reflected in the city park system, designed by Frederick Law Olmstead, and in homes designed by Frank Lloyd Wright and other noted architects.

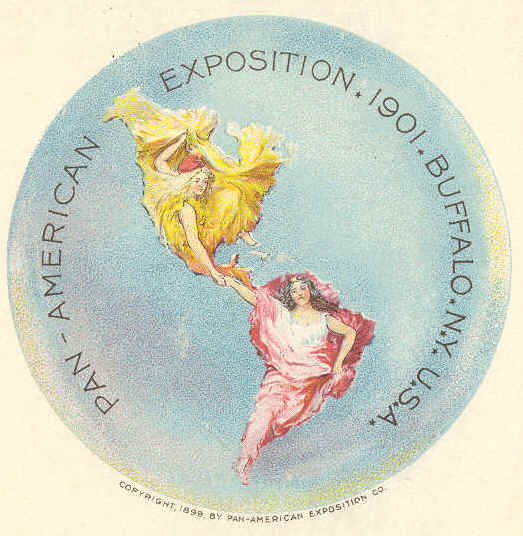

The eyes of the nation turned to Buffalo in 1901, when it hosted the Pan-American Exposition, a six-month fair. “Expositions are the timekeepers of progress,” President William McKinley said during his visit to the fair. Progress on display in Buffalo included thousands of electric bulbs lighting the fair’s buildings, and a new medical device called the X-ray machine.

McKinley was from Ohio, and a close associate of that state’s Sen. Mark Hanna, the powerful leader of the national Republican Party. McKinley visited the exposition several days, enjoying the exhibits and drawing huge crowds. Thousands lined up to shake the president’s hand at a reception in the Temple of Music. One of those was Leon Czolgosz, an avowed anarchist who had a gun in his hand, hidden beneath a handkerchief. He shot McKinley twice at close range. Eight days later, the president was dead.

While McKinley visited Buffalo, his vice-president, Theodore Roosevelt, was vacationing nearby in the Adirondacks. Roosevelt was young, spirited and ambitious. A reform-minded Republican, Roosevelt had ruffled feathers in the GOP patronage machine while serving on the Civil Service Commission and had crusaded against corruption as a New York City Police Commissioner. After he became a hero fighting in Cuba during the Spanish-American War, he returned to politics, running successfully for governor of New York with the reluctant blessing of Thomas Platt, boss of the New York GOP.

Hanna, an ally of the big corporations known then as trusts, had no use for the independent-minded Roosevelt. Platt wanted TR out of New York, where he was a threat to the GOP machine and Tammany Hall. So they maneuvered Roosevelt into what was thought to be a powerless dead end: the vice presidency.

Six months after he was sworn in for that office, Roosevelt found himself in a parlor in Buffalo being sworn in as president. At 42, he was the youngest president ever.

Roosevelt turned out to be one of America’s most consequential presidents. He bucked the bosses, reined in the trusts and created new regulatory agencies. He raised America’s profile as a world power. He built the Panama Canal. He expanded the formal, and informal, powers of the president, using its “bully pulpit” – a term he coined – to involve the White House in such matters as college football and a push for “simplified spelling.”

A white obelisk now stands in front of City Hall, a monument to William McKinley. The house where Teddy Roosevelt began his presidency still stands on Delaware Ave. with many of its original furnishings intact, a museum to the moment two bullets and the Constitutional order changed the path of American history.

Buffalo kept growing after the 1901 Exposition, with manufacturing joining transportation as drivers of a booming economy. In 1950, its population peaked at 580,000, but things went downhill from there. In 1959, the St. Lawrence Seaway opened, connecting the Great Lakes directly to the Atlantic, bypassing Buffalo and putting the Erie Canal out of business. Infrastructure gives, and infrastructure takes away. Then the manufacturing jobs moved away, first to the South, then abroad. Buffalo’s population is now half what it was in 1950.

Buffalo is still kicking. It has redeveloped part of its riverfront into a hip entertainment district. It has replaced many lost manufacturing jobs with jobs in education, health care and high tech. It’s got pro sports teams, ethnic neighborhoods and a sense of identity forged through hard times and long snowy winters.

Its future is hard to predict, but at least its past is easy to see.

Rick Holmes can be reached at rick@rickholmes.net. You can follow his journey at www.rickholmes.net. Like him on Facebook at Holmes & Co, on follow him on Twitter @HolmesAndCo.