America’s founding scientists

By Rick Holmes

Nov. 30, 2018

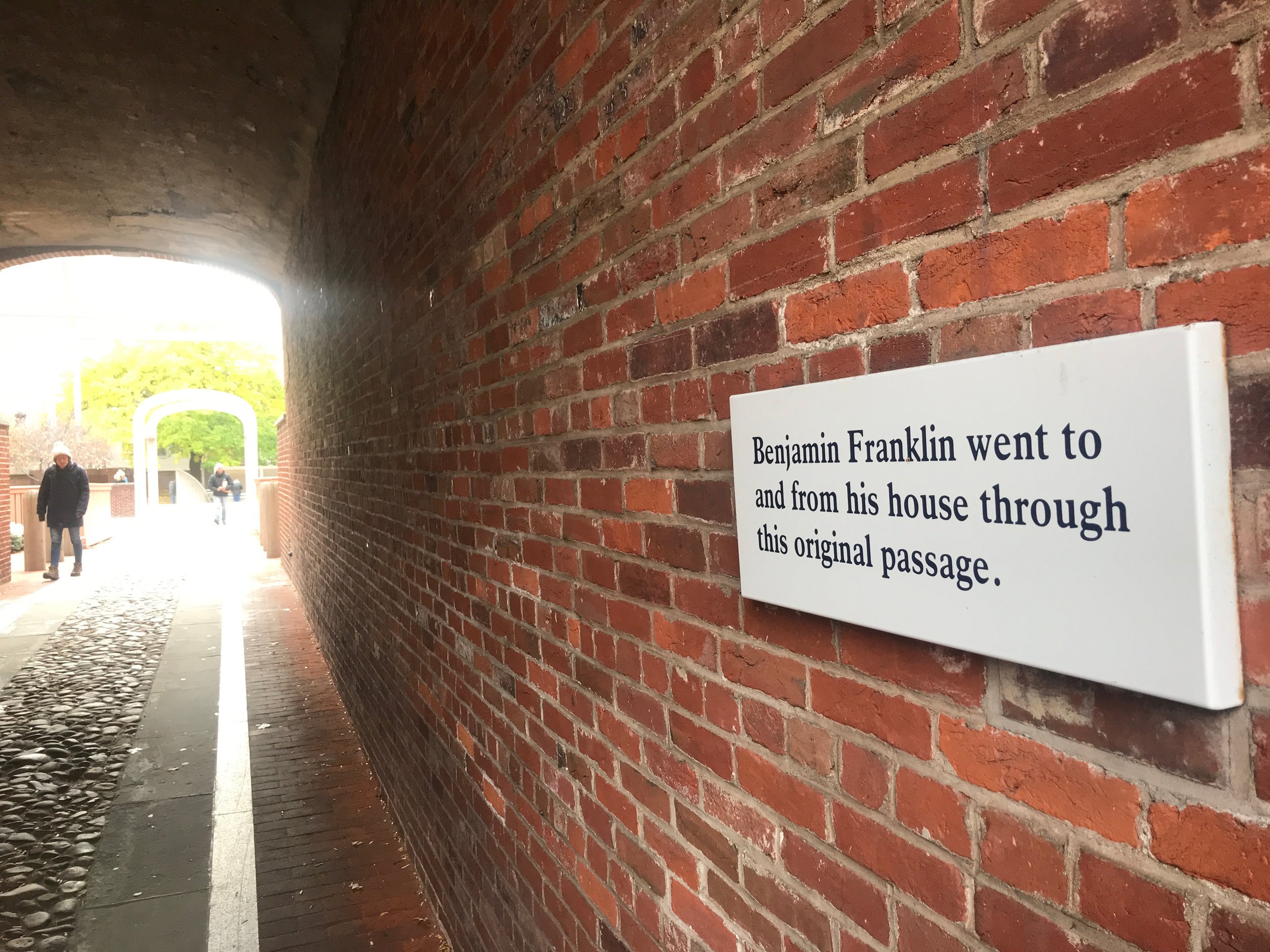

Philadelphia – Franklin Court sits on Market Street, a short walk up from the Delaware River waterfront where young Benjamin Franklin came ashore. Franklin’s house is long gone, but a brick passageway to a courtyard remains, along with some reconstructed facades of the buildings that held some of his many enterprises: his print shop, postal office, houses occupied by his family and some spaces to rent.

There’s a museum that tells Franklin’s story, and historical markers that provide context.

But there’s nothing that says here lived a giant. His popular image is similarly modest. People think of Franklin as a character actor in the pageant of America’s founding. He’s the old bald guy with the spectacles, spouting witty aphorisms.

But Franklin was so much more. Those weren’t just spectacles, they were bifocals, and he didn’t just wear them, he invented them. The aphorisms came from his series of books, “Poor Richard’s Almanack.” It wasn’t just America’s first best-seller, it was a best-seller in Europe as well.

Franklin was many things: publisher, diplomat, political philosopher, civic leader, problem-solver. Consider fire, perhaps the biggest threat to cities like Philadelphia. Franklin organized the city’s first volunteer fire department and its first fire insurance company. Then he invented the lightning rod, eliminating one of the greatest causes of structure fires.

But it was his work as a scientist that made Franklin the most famous American of his time. He was a prodigious and practical-minded inventor. He studied everything from ocean currents and population projections to wave theory and meteorology. He didn’t just experiment with electricity, he nearly invented it. Franklin coined the terms battery, negative charge and positive charge.

The canon of modern conservative politics paints the Founding Fathers as evangelicals and priests who established a “Christian nation.” In reality, they were products of the Enlightenment, the cultural and intellectual wave that grew in opposition to Europe’s religious establishment. Like other Enlightenment thinkers, they were devoted to study and reason, experimentation and measurement. They brought the same discipline to the study of history, philosophy and public affairs that they brought to the study of the natural world.

It’s not that the leaders like Franklin, Thomas Jefferson and George Washington lacked faith. They were deists with strong opinions about virtue and morality. But they drew careful distinctions between facts and beliefs. They were scientists, not preachers.

Jefferson was also an inventor, designing furniture and farm equipment. Franklin founded the American Philosophical Society to encourage science and Enlightenment ideals; Jefferson was a member for 35 years. Jefferson took temperature readings twice a day, wherever he was. He measured precipitation, winds, humidity. He catalogued wild plants and tracked bird migrations. Both he and Washington were students of agricultural science.

Our founding scientists gave us a government designed to operate on facts and reason. Today, that government collects data constantly. It hires and contracts with thousands of scientists. The Library of Congress – started with Jefferson’s own book collection – was created as a repository of knowledge intended to guide the nation’s decision-makers.

In that spirit, Congress requires 13 government agencies report every four years on the state of the climate. Their latest assessment, 1,656 pages of data and analysis, concludes that climate change is real and poses a grave threat to the nation’s environment and economy.

But while you’ll find plenty of scientists in Washington, you won’t find one in the Oval Office.

It took 19 months for President Donald Trump to nominate a White House science advisor, and his nominee is still awaiting Senate confirmation. If Trump has spoken with any scientists about the conclusions in the climate report, he hasn’t said so. You can bet he hasn’t read it. But he says he doesn’t believe it.

“I have a natural instinct for science,” Trump said in a recent interview. “One of the problems that a lot of people like myself,” Trump told the Washington Post, “we have very high levels of intelligence but we’re not necessarily such believers” when it comes to climate change. Because he’s not a believer, he tried to bury the climate report by releasing it the day after Thanksgiving. Because of his beliefs, he’s using his executive powers to increase the greenhouse emissions scientists say are responsible for climate change.

A few days before the climate report was released, the scientists at NOAA reported that October was the 406th consecutive month that global temperatures were warmer than the 20th century average. That means anyone younger than 33 has never experienced a month with cooler than average global temperatures.

But it was chilly that day in New York, so the president sent out a tweet: “Whatever happened to Global Warming?”

Franklin and Jefferson knew how to read a thermometer. They knew the difference between weather and climate. They knew that temperature readings were matters of fact, not belief. This can’t be the kind of president they had in mind.

Rick Holmes can be reached at rick@rickholmes.net. You can follow his journey at www.rickholmes.net. Like him on Facebook at Holmes & Co, on follow him on Twitter @HolmesAndCo.