One nation, divisible

Why did the South secede?

By Rick Holmes

Dec. 8, 2017

Charleston, SC - I’ve looked out from the Sunken Road in Fredericksburg, where Confederate soldiers, dug in on the high ground, mowed down advancing Union troops like they were targets at a carnival shooting gallery. I’ve looked down from Little Round Top in Gettysburg over fields that earned new names in July 1863: the Slaughter Pen and the Valley of Death.

I’ve walked streets in Richmond that remember the sting of defeat. I’ve looked down rows of silent graves in Shiloh, Winchester, Wilmington and Gettysburg. I’ve walked the blood-soaked ground of Spotsylvania County, Virginia, where three battles in three weeks resulted in more than 60,000 American casualties.

And at each stop on my Civil War tour, I found myself asking, “Why?”

Why was all this bloodshed inevitable? Why couldn’t the politicians compromise? Why were the ties binding Americans so weak that the people of 11 states tried to sever them?

I brought my questions to the place where it all began. South Carolina was the first state to secede, and Charleston Harbor saw the war’s first battle.

I asked the rangers at Fort Moultrie and Fort Sumter, the giving and receiving ends of the cannon fire that launched the war, why South Carolina had seceded, and they delivered a familiar list of disagreements and grievances, from the Missouri Compromise to John Brown’s Raid.

I asked a historian in Richmond and he put it more succinctly: “Secession caused the Civil War,” he said, “and slavery caused secession.”

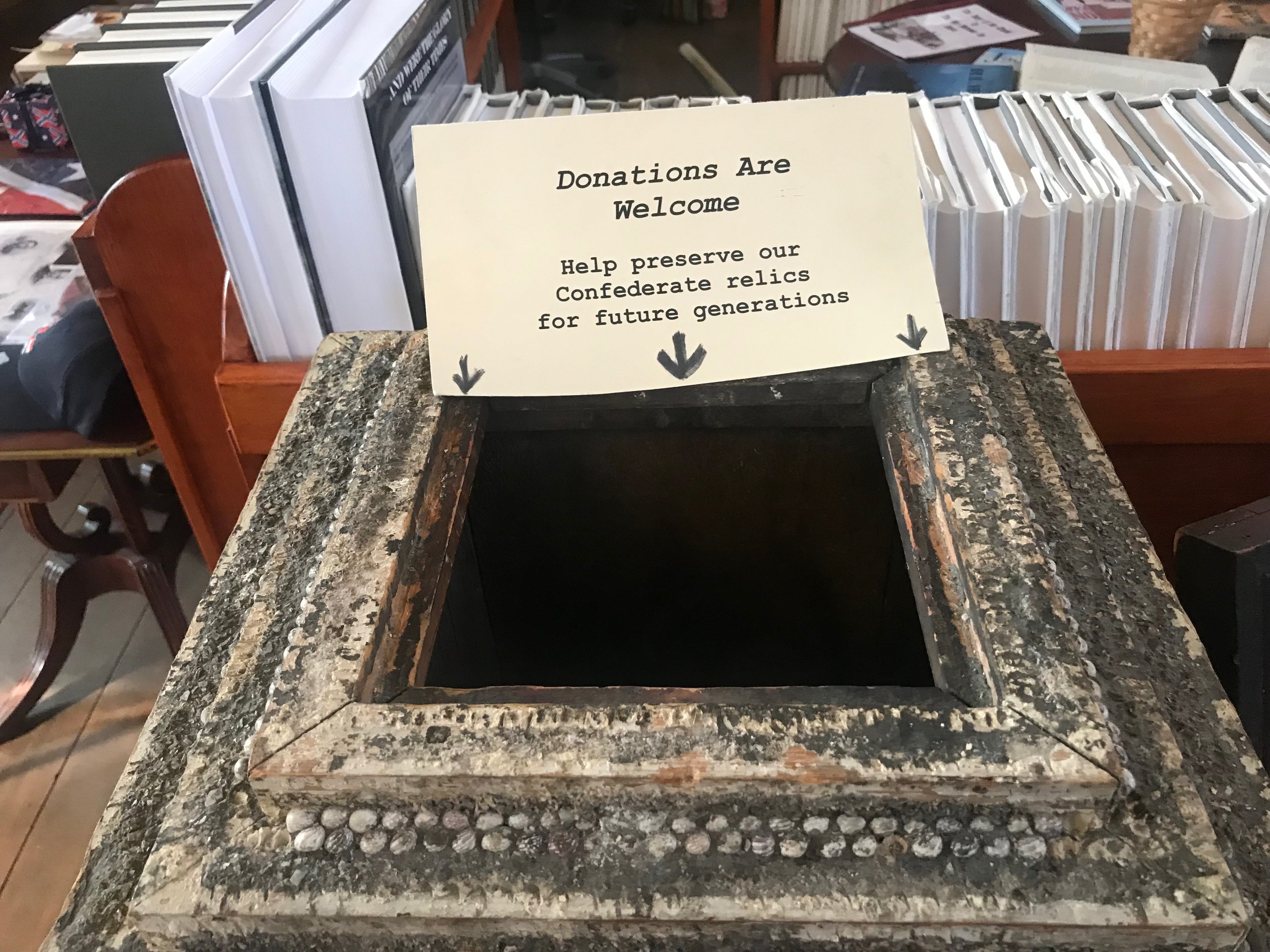

I asked two members of the Daughters of the Confederacy who welcomed me to the Museum of the Confederacy, housed in an ancient meeting hall above Charleston’s historic market. The building was built in 1841 and was where most of the Charleston boys came to sign up to join the Confederate Army.

“It was the tariffs,” said one of the women, whose Charleston roots date back to 1680. “It wasn’t about slavery until Lincoln made it about slavery.”

“We just wanted to be independent,” she said, “and if it were happening again today I’d be the first to sign up.”

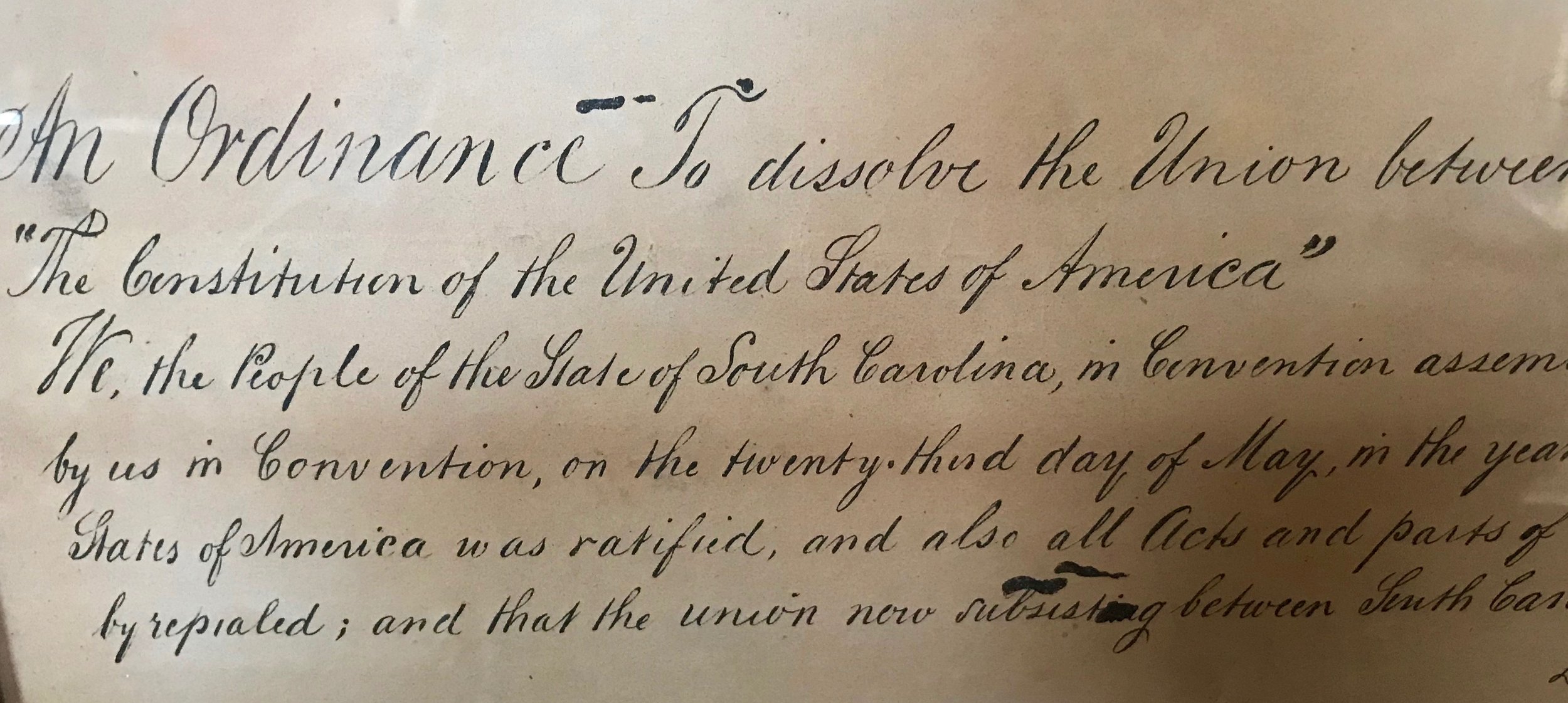

The tariff myth, cited by supporters of the Confederacy for 150 years, isn’t convincing. The Morrill Tariff wasn’t enacted until three months after South Carolina seceded, and wouldn’t have passed the Senate if senators from seceding states hadn’t already resigned. And while the Museum of the Confederacy has a framed version of South Carolina’s resolution of secession, I didn’t see a copy of the “Declaration of the Immediate Causes” for secession, adopted several days later, which says nothing about tariffs but plenty about “an increasing hostility on the part of the non-slaveholding States to the institution of slavery.”

There was no immediate threat to slavery in South Carolina or other states in 1860, even with Lincoln as president. Abolitionists were nowhere close to a majority in Congress, and no court ruling threatened the status quo. Indeed, an amendment to the Constitution had already been approved by large majorities in Congress to protect slavery forever where it currently existed. Lincoln had said he would support it. That, along with several other proposed compromises, died with the first shots on Fort Sumter.

The “immediate cause” that bothered Carolinians most was lax enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act, which required officials in all states to detain and return escaped slaves. Their valuable property was slipping away on the Underground Railroad. Abolitionist Northerners were declaring what you might call “sanctuary cities,” where escaped slaves could find relative safety. That trend directly threatened the value of their property.

Plus, Abraham Lincoln had been elected, though without votes from most Southern states, which had kept his name off the ballot. The real debate in the 1860 election was over expanding slavery to new states being created in the West. That wasn’t a short-term threat to slavery in the South, but it was a long-term threat to the political power of slave state politicians, and that loss of clout threatened the prosperity of the Southern elite.

So they tried to dissolve the United States in order to protect future profits? Was secession a political gamble serving only the interests of the 3 percent of the population who owned 95 percent of the slaves?

If so, secession was a folly that turned into a disaster. The next question is why so many people still celebrate it.

Rick Holmes can be reached at rick@rickholmes.net. You can follow his journey at www.rickholmes.net. Like him on Facebook at Holmes & Co, on follow him on Twitter @HolmesAndCo.