Trump and Lee on Monument Avenue

By Rick Holmes

May 3, 2019

Richmond, Va. – Robert E. Lee hasn’t seen a string of defeats like this since 1865.

His statues have fallen in Baltimore, Memphis, New Orleans, Charlottesville and other places where his army of Lost Cause loyalists no longer control the territory. Sometimes they’ve come down after bitter battles in courts and state legislatures. Sometimes they’ve disappeared quietly in the dead of night, with only a handful of bitter-enders on hand to watch.

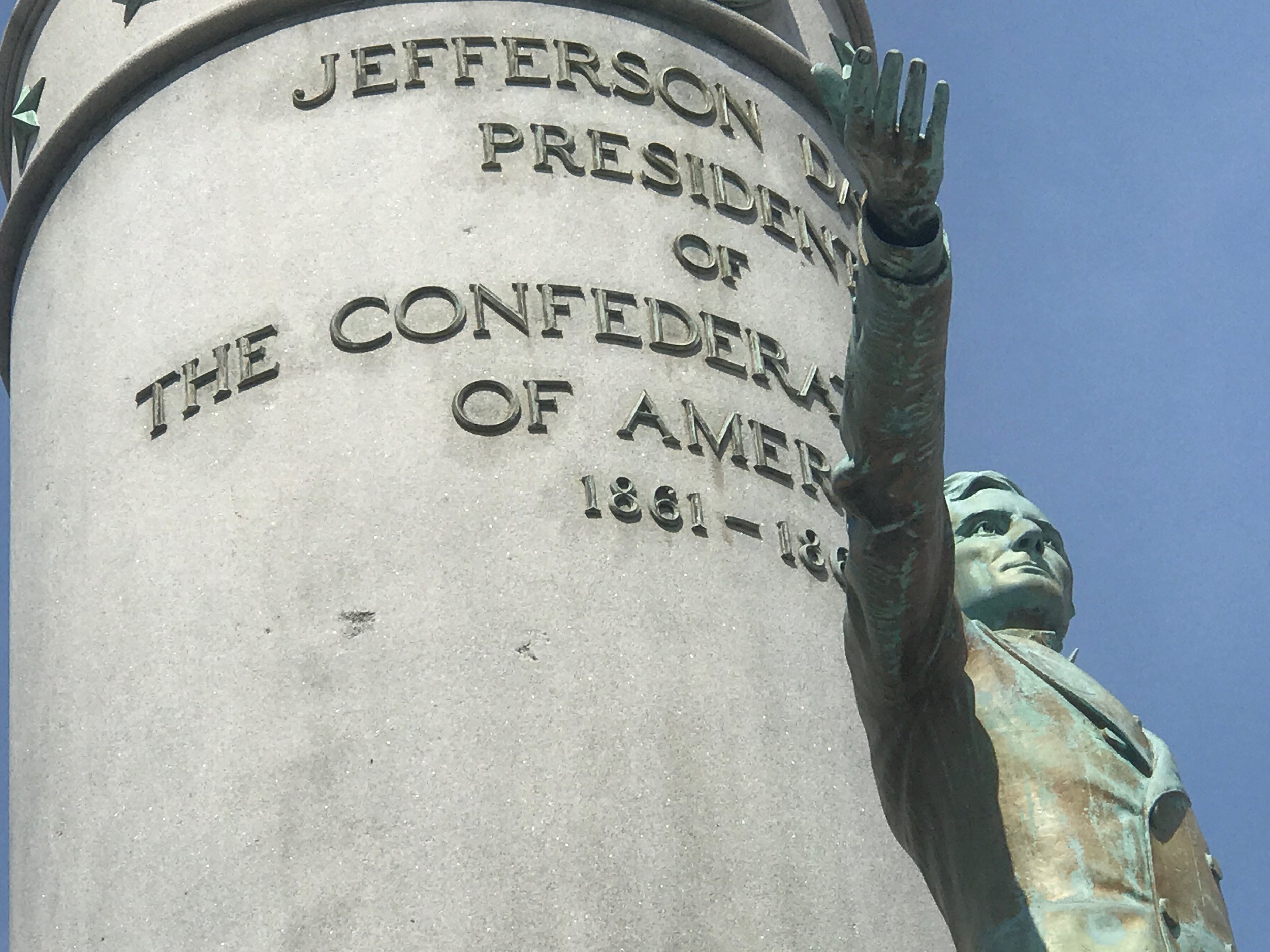

The old general still protects Richmond from his perch astride a horse, high above a traffic circle on Monument Avenue. Other traffic circles nearby are guarded by his generals, Stonewall Jackson and J.E.B. Stuart, and his commander, Jefferson Davis, the first and last president of the Confederate States of America. Even here, Lee’s position is weaker than it’s ever been.

But at least he’s got Donald Trump by his side.

Monument Avenue was built decades after Lee surrendered and Davis fled the Confederate Capital. It was conceived as a real estate development more than a historical park, but the cast-iron Confederates proved a potent draw. When the Lee statue was unveiled in 1890, 100,000 people came out to cheer.

By then, Lee had been transformed from historical figure to mythic hero. Lee was the embodiment of the Lost Cause, as noble as the Old South. Lee was opposed to slavery and secession, the legend said, but his love for his home state forced him to side with the Confederacy. He was a brilliant general, defeated, as one of the Monument Avenue memorials says, only after “four years of unflinching struggle against overwhelming odds.”

The Lost Cause version of American history romanticized plantation life, whitewashed slavery, and argued that secession was a principled defense of states’ rights. It justified taking away the rights of emancipated slaves and the institutionalized racism of Jim Crow laws. It embraced the Ku Klux Klan’s reign of terror. That was the context in which the statues of Lee and other Confederate leaders appeared, symbols of Southern pride and white supremacist intimidation.

The Lost Cause gained wide acceptance in the South, spread across the country and influences our politics still. Historian Edward Bonekemper III calls it “the most successful propaganda campaign in American history.”

Trump enlisted Lee in response to continuing criticism over his “fine people on both sides” response to white supremacist violence in Charlottesville in 2017. "I was talking about people that went because they felt very strongly about the monument to Robert E. Lee, a great general," Trump said. "Whether you like it or not, he was one of the great generals."

Actually, whether the president likes it or not, Lee’s reputation has been taking a beating from historians. His own writing contradicts the notion that he opposed slavery. He was far from a benign slave-owner: He systemically broke up enslaved families, violating a family tradition of keeping families intact. He oversaw brutal whippings of his slaves, ordering brine be poured on the cuts left by the lash.

Historians note that other officers raised in the South were faithful to the oaths they took to defend the United States and its Constitution while Lee chose treason. For 50 years, military historians have questioned Lee’s generalship, criticizing both his offensive forays into the North and his obsessive defense of Virginia.

Not all statues of Confederate generals are misplaced. There’s one I like in Gettysburg in which he sits astride Traveller, gazing over the field where Pickett’s Charge produced a Confederate bloodbath Lee should have seen coming. He dismounted and walked among the retreating men, apologizing for his terrible misjudgment.

Trump, who has never shown much interest in history, is engaging in his own historical revisionism, pretending that the white supremacists in Charlottesville carrying tiki torches and chanting “Jews will not replace us” were mostly concerned for Bobby Lee’s reputation.

But Lavar Stoney, mayor of Richmond, knows better. He responded to Charlottesville by naming a commission to consider what to do about Monument Avenue. “The statues on this beautiful street are Lost Cause myth and deception masquerading as history,” he said. “Something needs to change.”

The commission called for the removal of the statue of Jefferson Davis, a tribute to a non-Virginian most heavily steeped in Lost Cause mythology, and for the erection of plaques putting the other statues in historical context. But when I visited it a few weeks ago, nothing had changed on Monument Ave.

So far, Richmond has chosen to solve its historical monuments problem by addition instead of subtraction. They’ve added a memorial of tennis legend Arthur Ashe, a Richmond native and African American, to the Monument Ave. lineup. Mayor Stoney is focusing public investment on new historical markers in Shockoe Bottom, the site of Richmond’s biggest slave market. Good for him.

Taking down Lost Cause memorials isn’t “erasing history,” as some claim. Such statues are civic expressions, not history, and there’s nothing wrong with officials charged with administering public parks revising the sentiments expressed by their long-dead predecessors.

Neither Robert E. Lee nor Donald Trump will ever be erased from America’s history texts. We erase history only when we choose not to tell the stories of the people who came before us, or when we stop arguing about their meaning.

Rick Holmes can be reached at rick@rickholmes.net. You can follow his journey at www.rickholmes.net. Like him on Facebook at Holmes & Co, and follow him on Twitter @HolmesAndCo.